.

.

.

1. The remains of the north and south walls of Christ Church, seen from the London Stock Exchange in Newgate Street.

.

4. The Christ Church site seen from the BT Headquarters at the corner of Newgate Street and King Edward Street.

.

7. Christ Church from King Edward Street: the exterior as it appeared prior to demolition of the east and south walls. The picture uses a wartime photo, retouched to remove debris from the Blitz. The opening under the end window is added to show how the pedestrian route through the church site could be accommodated in a reconstruction.

.

.

8. Drawing by Peter Shepheard of the nave of Christ Church as a memorial garden, from Bombed Churches as War Memorials, Architectural Press, 1945. The drawing was printed back-to-front in the book, but has been corrected here.

.

10. Main drawing – the exterior of Christ Church after reconstruction of the missing walls for the Citizens’ Memorial – view from corner of Newgate Street and King Edward Street; lower right, outline plan at street level.

2 – The canopied walkway

.

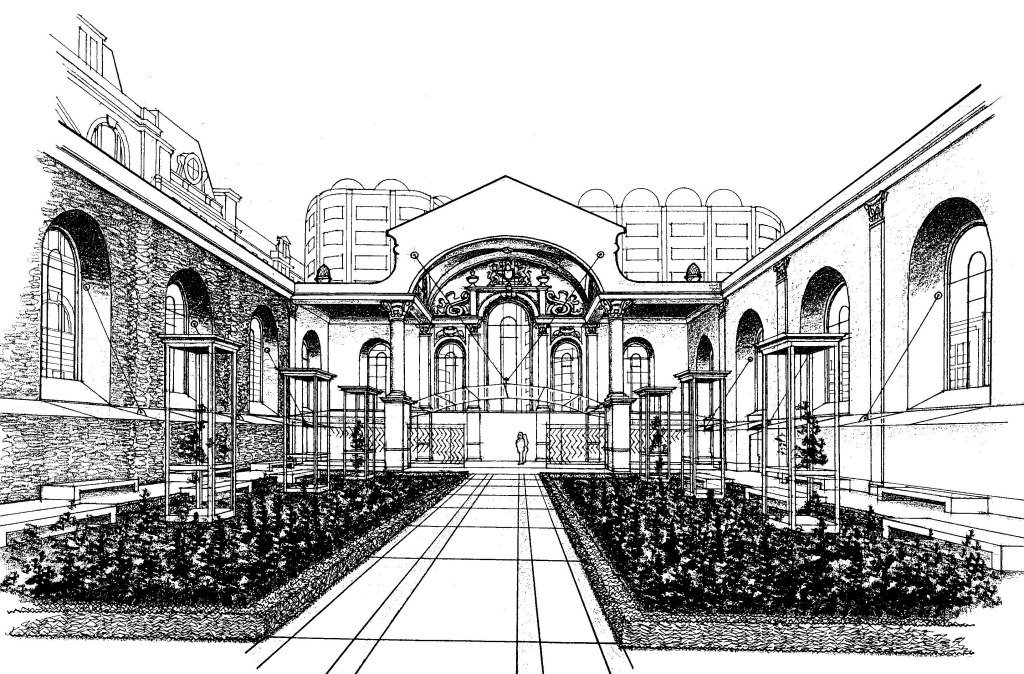

11. This drawing shows how the garden within Christ Church might look with the elements of the church fabric reconstructed for the Citizen’s Memorial. The view is from a position near the tower, looking east, with Newgate Street on the right.

3 – The garden sanctuary

Click once or twice on the images for full-size picture.

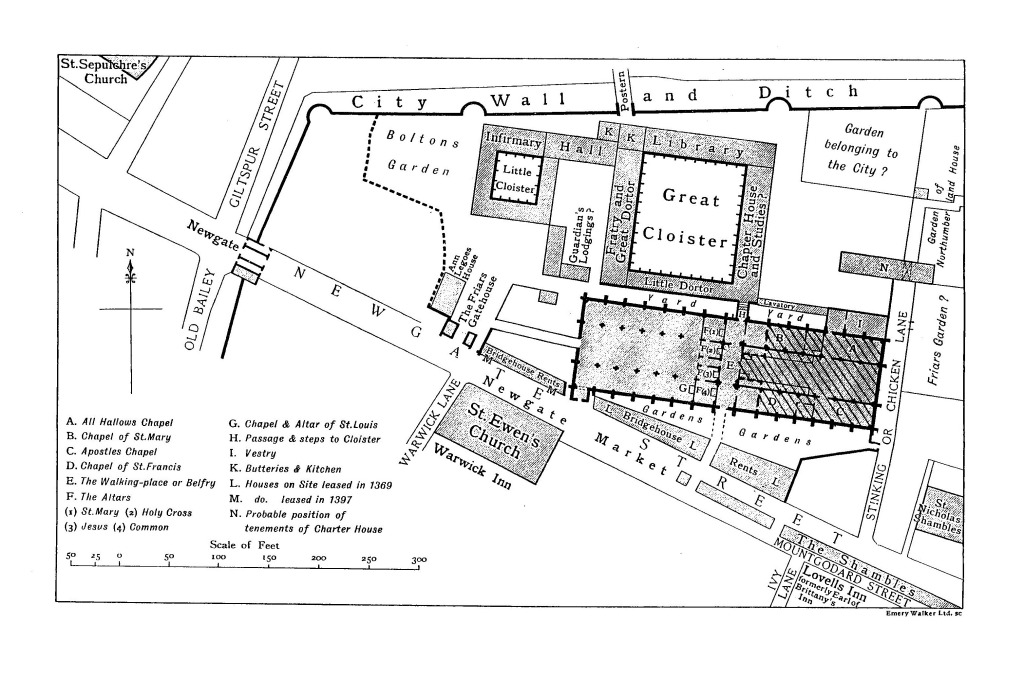

1. Outline plan of Greyfriars, from The Grey Friars of London by Charles Kingsford, Aberdeen University Press, 1915.

.

Following its destruction in the Great Fire of London of 1666, Christ Church was rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren. In the above plan, the footprint of Wren’s church is shown hatched. The interior was gutted by fire in the Second World War, with only the tower and outer walls only remaining intact. Large sections of these walls were demolished in 1973 for road-widening. In 2001 the footprint of the church was reinstated and low walls were built to mark the missing fabric. The surviving ruins are now a public garden.

The medieval church

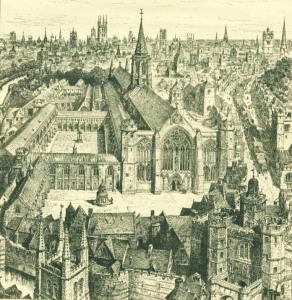

2. The church of the friary of Greyfriars, destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, looking east. The City wall is clearly depicted at the bottom of the picture, with Newgate Street on the right side. Wren’s church occupies only the site of the choir of the medieval church, beyond the spire.

.

Franciscan friars first settled on a site close to the City wall in 1225, on land granted by John Iwyn, a rich mercer. Their first church was built using funds given by Sir William Joyner, Lord Mayor of London in 1239, but it was soon replaced by a bigger building, begun in 1306 and consecrated in 1326. The new church, built in the gothic style, was the second largest in size and importance in medieval London after Old St Paul’s, measuring 300 feet (91 m) long and 89 feet (27 m) wide, and had at least eleven altars. It was built partly through the beneficence of Marguerite of France, second wife of King Edward I. She was buried at the church, as were the remains of three other queens – Isabella, widow of Edward II; the heart of Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III, which is said to have been interred beneath the altar; and Joan de la Tour, Queen of Scotland and daughter of Edward II. London’s citizenry was said to have aspired to be connected with the church, and many other illustrious people were interred there. A figure widely known from medieval history, Sir Thomas Malory, the chronicler of King Arthur, was interred near the south-west corner of the medieval church. Other burials of the famous or the notorious included Isabella, Lady de Coucy, eldest daughter of Edward III; Margaret, Duchess of Norfolk, granddaughter of Edward I; the prophetess Elizabeth Barton, the ‘Mad Maid of Kent’; the celebrated beauty and socialite Venetia Stanley; courtier, diplomat and natural philosopher Sir Kenelm Digby; and theologian Richard Baxter. The friary was dissolved in 1538 during the English Reformation. It had included a university and a library, founded in 1429 by Richard Whittington, Lord Mayor of London, and is said to have equalled Oxford in importance and status at the time. The church and its fittings suffered heavy damage during the time of the dissolution. Tombs disappeared, sold for their marble and other valuable materials, and monuments were defaced. In 1546 Henry VIII gave the priory and its church, along with the churches of St Nicholas Shambles and St Ewin, Newgate Market, to the City Corporation. A new parish of Christ Church was created, incorporating those of St Nicholas and St Ewin, and part of that of St Sepulchre. The old priory buildings were later used to house Christ’s Hospital School, founded in 1552 by Edward VI, and the church became its pupils’ principal place of worship.

.

3. Christ’s Hospital School in 1770.

Wren’s church

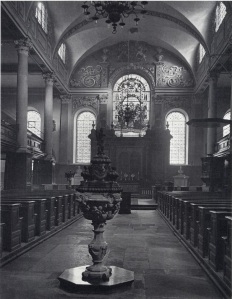

The medieval church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. Reconstruction was assigned to Wren, who oversaw a decades-long programme that rebuilt St. Paul’s Cathedral and approximately 50 other parish churches in the fire-devastated area. The parish was united with that of St Leonard, Foster Lane, which was not rebuilt. There appears to have been some debate about the form the new Christ Church should take. A surviving unused design shows a structure considerably larger than what was eventually built. Parishioners raised £1,000 to begin work on the design that in the end was selected. To save time and money, the foundations of the gothic church were partially re-used. Wren’s building is less than half the length of its predecessor, with its tower being built at the former crossing and its nave on the site of the choir. Significantly however, in basing the new church on the earlier foundations, he preserved the ground plan of the medieval church – the dimensions of its six bays and the setting-out of the columns are precisely as they were in the medieval church. The new church and tower – not yet with its steeple – were completed in 1687, at a total cost of £11,778 9s. shillings 7¼d. Occupying only the eastern part of the site of its predecessor, Wren’s building measured 114 feet (35 m) long and 81 feet (25 m) wide, with the western part of the medieval site becoming its churchyard. The tower, rising from the west end of the church, had a simple round-arched main entrance and, above, windows decorated with neoclassical pediments. Large carved pineapples, symbols of welcome, graced the four roof corners of the main church structure. Unique among the Wren churches, the east and west walls had buttresses. The steeple, standing about 160 feet (49 m) tall, was finished in 1704 at an additional cost of £1,963, 8s. 3½ d. It has three diminishing storeys, square in plan, the middle one with a freestanding Ionic colonnade. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, the celebrated chronicler of England’s architecture, commented that it is one of the most splendid in London, and that it could be called a square version of that at St Mary-le-Bow. The interior was divided into nave and aisles by Corinthian columns, whose square-section bases were raised to gallery level, and innovation introduced here by Wren to make a more satisfactory junction between columns and gallery. The aisles had flat ceilings, while the nave ceiling had a shallow cross-vault, the only example of this type in Wren’s basilica-style churches, and perhaps a reminder of its medieval predecessor. The north and south walls had large round-arched windows of clear glass, which allowed for a brightly lit interior. The east end had trinity windows, a large wooden altar screen and a carved hexagonal pulpit, reached by stairs. There was elaborate carved wainscoting. A pavement of reddish brown and grey marble to the west of the altar rails was said to date from the original gothic church. Steep galleries stood over the north and south aisles, built at special request of the officers of Christ’s Hospital as seating for the school’s students. Pews were said to have been made from the timbers of a wrecked Spanish galleon. The organ, on the west wall over the main nave door, was built by Renatus Harris in 1690, according to a pre-war guide to the church.

Wartime damage

The church was severely damaged in the Blitz. On the night of 29th December 1940, during one of the Second World War’s fiercest air raids on London, an incendiary bomb struck the roof and tore into the nave. The woodwork of the church soon created an inferno. Much of the surrounding neighbourhood was also set alight by incendiaries – a total of eight Wren churches burned that night. Fire-fighting resources were desperately stretched, and the church could not be saved. Its roof and vaulting collapsed into the nave; the tower and four main walls, built of stone, remained standing but were smoke-scarred and weakened. The only fitting known to have been saved from Christ Church was the cover of the finely carved wooden font, topped by a carved angel. It was recovered by an unknown postman who ran inside as the flames raged. Today it can be seen in the porch of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate.

.

10. Two firemen hosing down smouldering rubble in the nave of Christ Church on the day following the fire.

.

11. Christ Church after the fire of 29 December 1940, looking east.

.

12. This historic photo looks north from St Paul’s across Paternoster Square, taken soon after 29 December 1940. In the middle distance the tower of Christ Church can be seen, and just to its right is the shell of the nave, now the location of the proposed Citizens’ Memorial.

.

13. Christ Church font cover, saved by an unknown postman, and now in St Sepulchre-without-Newgate. Image 4 depicts where it had formerly stood, in the main aisle of the nave.

.

14. This picture of the east wall of Christ Church on King Edward Street was taken not long after Images 11 and 12 above. Despite the wartime detritus left on the pavement, it clearly conveys Wren’s strongly-modelled and dignified classical composition, which until its demolition by the City in 1973 made a significant contribution to the streetscape – it was a facade which was intended to be seen, unlike the north and south walls, which were thought likely to be hemmed-in by neighbouring buildings and were therefore finished in undressed stonework. Note that the church is abutted by the building on the left, resulting in the window of the adjoining bay having been blocked up. Note also the prominent buttresses, the pineapple vases on the corners, and the doorway under the left window, raising the question of whether this was an original feature.

.

15. A wartime view of King Edward Street looking south, probably also contemporaneous with Images 11 and 12. A high-explosive bomb has left a large crater in the middle of the street. To the left, St Paul’s is visible through the haze. To the right of centre is the east end of Christ Church, roofless. Silhouetted against the church is the statue of Rowland Hill, behind which on the right is the GPO Head Office.

The post-war period

In 1949, in a reorganisation of Church of England parishes in London, the authorities decided not to rebuild Christ Church. The remains of the church were designated a Grade I listed building in 1950. In 1954, the Christ Church parish was merged with that of the nearby St Sepulchre-without-Newgate. The steeple, still standing after the wartime damage, was dismantled in 1960 and reconstructed using modern construction methods. The twelve urns which had surmounted the entablature above the Ionic columns in its middle storey, and which had been taken down in 1814, were restored, through a private benefaction, with fibreglass replicas.

.

16. The steeple of Christ Church seen from King Edward Street, through the east window of the church. A photograph taken after the reconstruction of the tower in 1960. This view was created as a result of the destruction of the interior during WW2, and existed until the demolition of the east wall itself in 1973.

.

17. The environs of Christ Church from the air in the late 1940’s. The church is just to the right of the dome of St Paul’s.

.

18. ‘Christ Church, Newgate Street’ by John Piper. Oil on canvas, painted in 1941. The destroyed nave of the church, looking east – compare with the drawing by Peter Shepheard, Image 8 in the description text.

.

19. ‘Christchurch and Greyfriars’ by Edward Bawden. Drawing made in 1948. The artist succeeds in finding poetic touches on a grey, rainy day in post-war King Edward Street as postmen go about their duties.

.

20. This photo of King Edward Street looking south towards St Paul’s was published in 1956. Compare with Image 15 in the sequence, which was taken from the middle of the road. The east end of Christ Church, with the pediment above its east wall in side view, is seen between the statue of Rowland Hill and the GPO Head Office to the right, and is still part of the streetscape. The east wall of the church was a strong classical design, as other photos show, and was undoubtedly intended by Wren to be seen in conjunction with St Paul’s.

The site in recent times

The fortunes of the Christ Church site after the 1960’s have largely been dictated by the vagaries of planning decisions. In 1973 the surviving east wall, much of the south wall and part of the north wall were shamefully demolished to make way for a widening of King Edward Street and the access to it from Newgate Street. This meant that, until 2001, traffic encroached the church site to the extent of actually passing over its foundations at its south-east corner. In 1981, neo-Georgian brick offices were constructed against the south-west corner of the ruins, in imitation of the 1760 vestry house that had stood there. In 1989, the former nave area became a public garden. In 2002, the financial firm Merrill Lynch completed its new European headquarters on the adjoining site to the north and the west, largely occupied previously by premises of the General Post Office, and originally the site of the Greyfriars friary. In connection with a Section 106 planning agreement included in the project, the Christ Church site underwent a major renovation and some archaeological investigation in the former nave. King Edward Street was returned approximately to its former alignment, and the footprint of the church, as it had existed prior to the demolition of large sections of its external walls, was reinstated. However the original walls were not reconstructed, and instead low stone walls, one metre in height, were built to mark their position. King Edward Street being now wider than previously, its pavement was re-aligned through the church itself, an unusual situation resulting in pedestrians traversing the site where the altar had formerly stood. The churchyard was renovated and its metal railings restored. The church tower initially functioned as commercial space, but in 2006 work was completed to convert the tower and steeple into a residential apartment on ten levels. It was then sold by the City authorities into the private property market. The nave area continues to be used as a garden.